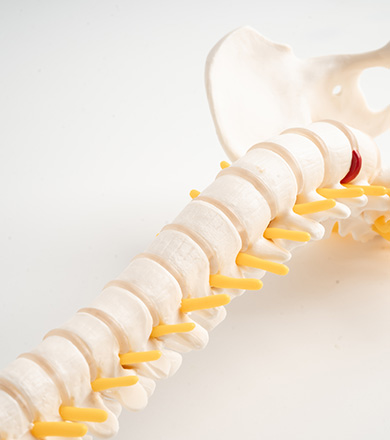

Pathology

Thoracic disc herniation occurs when the intervertebral disc in the thoracic spine (mid-back) protrudes or ruptures, compressing nearby nerve roots or the spinal cord. The thoracic spine consists of 12 vertebrae (T1-T12) and is less commonly affected by disc herniation compared to the cervical and lumbar regions due to its relative rigidity and limited range of motion. However, when herniation occurs, it can lead to significant neurological symptoms due to the narrow spinal canal in this region.

Etiology

The causes of thoracic disc herniation can be multifactorial, including:

Degenerative Disc Disease: Age-related wear and tear of the intervertebral discs, leading to disc desiccation, loss of disc height, and increased susceptibility to herniation.

Trauma: Sudden injury from falls, motor vehicle accidents, or sports activities can cause acute disc herniation.

Repetitive Stress: Chronic repetitive motions or lifting heavy objects can contribute to disc degeneration and herniation.

Genetic Predisposition: Family history of disc herniation or degenerative disc disease can increase the risk.

Poor Posture: Sustained poor posture, particularly when sitting or lifting, can put undue stress on the thoracic spine and lead to disc herniation.

Symptoms

Thoracic disc herniation can present a variety of symptoms, depending on the size and location of the herniation, including:

Mid-Back Pain: Localized pain in the thoracic region.

Radiating Pain: Pain that radiates around the chest or abdomen, sometimes mistaken for cardiac or gastrointestinal issues.

Numbness and Tingling: Sensory changes in the chest, abdomen, or upper back.

Weakness: Muscle weakness in the lower extremities, potentially affecting walking and balance.

Myelopathy: Severe cases can lead to spinal cord compression, causing significant neurological deficits such as difficulty walking, loss of bladder or bowel control, and increased reflexes.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnosing thoracic disc herniation typically involves:

Medical History and Physical Examination: Assessing symptoms, medical history, and conducting a physical exam to evaluate neurological function.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The gold standard for visualizing disc herniation and its effect on the spinal cord and nerve roots.

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Used when MRI is contraindicated or for detailed bony anatomy evaluation.

X-Rays: To assess spinal alignment and rule out other conditions such as fractures.

Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Studies: To assess the functional impact of the herniation on nerve roots.

Conservative Treatment

Many cases of thoracic disc herniation can be managed with conservative treatments, including:

Medications:

Pain Relievers: NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or opioids for severe pain.

Muscle Relaxants: To relieve muscle spasms.

Nerve Pain Medications: Gabapentin or pregabalin for neuropathic pain.

Physical Therapy: Exercise programs to strengthen back muscles, improve flexibility, and reduce pain.

Activity Modification: Avoiding activities that exacerbate symptoms and incorporating ergonomic adjustments.

Epidural Steroid Injections: To reduce inflammation and pain around the affected nerve roots.

Heat and Cold Therapy: To alleviate muscle tension and pain.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery may be necessary for patients with severe or persistent symptoms, neurological deficits, or myelopathy. Surgical options include:

Discectomy: Removal of the herniated portion of the disc to decompress the spinal cord or nerve roots.

Laminectomy: Removal of part of the vertebra (lamina) to access and decompress the herniated disc.

Fusion Surgery: Stabilizing the affected vertebrae by fusing them together, often used in conjunction with discectomy or laminectomy to provide long-term stability.

Minimally Invasive Techniques: Endoscopic or microscopic procedures to reduce recovery time and surgical risks.

Postoperative Care

Postoperative care is crucial for recovery and includes:

Rehabilitation: Physical therapy to restore strength, flexibility, and function.

Pain Management: Medications and techniques to manage postoperative pain.

Regular Follow-Up: Monitoring for complications or recurrence through clinical evaluations and imaging studies.

Conclusion

Thoracic disc herniation, though less common than cervical or lumbar herniations, can cause significant pain and neurological deficits. Understanding the pathology, etiology, and treatment options is essential for effective management. Conservative treatments can provide relief for many patients, while surgical intervention is sometimes necessary for severe cases. A comprehensive approach, including accurate diagnosis, individualized treatment plans, and appropriate postoperative care, is crucial for achieving the best outcomes for patients with thoracic disc herniation.